This post is also available in: Français Español العربية فارسی Русский Türkçe

How many Jews did the Nazis and their collaborators murder at the Operation Reinhard death camps of Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor?

Holocaust deniers claim that the number of Jews murdered at Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor (about 800,000, 450,000, and 170,000 respectively) have been “simply invented” and are only “numbers plucked entirely from thin air.” Deniers say that there is “no documentary or physical evidence” for these figures.[1]

How we know how many Jews were murdered at Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor?

We do not know the exact number of Jews that the Nazis and their collaborators murdered at the three Operation Reinhard death camps. Why? Odilo Globocnik, the head of Operation Reinhard, ordered that most of the records be destroyed. Most historians and investigators who attempted to calculate a death toll directly after the war had little documentary evidence with which to work. They reconstructed the number of victims based on educated guesses for the number of transports and the average size of a transport. They coupled these reconstructed figures with eyewitness testimony from survivors and perpetrators. This method led to numbers that were often too high. However, newly-accessible Nazi documents have allowed modern historians to make more accurate—although not perfect—calculations.

![Deportation of Jews from Marseille, France. Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-027-1477-21 / Vennemann, Wolfgang / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.hdot.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/wiki_DeportationMarseille_OR3.jpg)

Deportation of Jews from Marseille, France. Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-027-1477-21 / Vennemann, Wolfgang / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Nazi documentation about the number of Jews murdered in the death camps:

There are two critical primary documents that provide detailed evidence about the number of Jews murdered at the Operation Reinhard death camps through the end of 1942. These primary documents are:

- The Höfle telegram of January 11, 1943

- The Korherr Report of March 1943

The Höfle telegram:

Researchers discovered this telegram in 2000 in a batch of newly-declassified World War II documents from the Public Records Office in Kew, England. The telegram had been intercepted and decoded by the British, who did not understand its implications at the time and filed it away.[2]

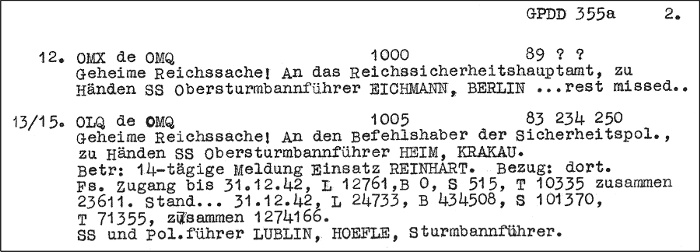

Hermann Höfle, Odilo Globocnik’s adjutant in Lublin, Poland sent the telegram to Adolf Eichmann in Berlin, Germany on January 11, 1943. The telegram was stamped “State Secret.” It listed the number of arrivals at the Operation Reinhard death camps (Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor) and Majdanek (a concentration camp in Lublin) during the last two weeks of December 1942. Höfle also provided the total number of Jews who had been shipped to these camps up to December 31, 1942. Höfle’s figures were as follows:

Previous two weeks Total until December 31, 1942

(L)ubin……………………………12,761………………………………………………………………………….24,733

(B)elzec………………………………..0………………………………………………………………………….434,508

(S)obibor……………………………515…………………………………………………………………………..101,370

(T)reblinka………………………..10,335………………………………………………………………………..713,555

Total……………………………….23,611…………………………………………………………………..1,274,166

Telegram, January 15, 1943 Hermann Höfle (1911–1962) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

For Höfle’s larger figures, we will only concern ourselves with Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.

Belzec: The first transport arrived on March 17, 1942 and the last transport arrived in the first half of November 1942. Thus, Höfle’s number of 434,508 victims at Belzec is a reasonable total for the lifetime of the camp.

Sobibor: The first transport arrived at the beginning of May 1942 and the transports continued off and on until October 1943. Recent research indicates that transports from France, the Netherlands, Yugoslavia, Poland, Lithuania and Belarus arrived in 1943 adding another 68,795 victims, for a total of 170,165 over the lifetime of the camp.[3]

Treblinka: The first transport arrived on July 23, 1942 and the last transport arrived on August 21, 1943. Höfle gave a figure of 713,555 victims to the end of December 1942. Many of the transports in 1943 have been identified and a minimum of at least 71,000 victims can be added for a working total of about 784,555 over the lifetime of the camp.[4]

Every single transport to the three camps is not known. But the evidence shows that a minimum of 1,389,228 Jews were murdered in these three camps.

An examination of the Korherr Report:

Richard Korherr was a statistician in the Third Reich. In March 1943, he was charged by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, with preparing a progress report on the Final Solution. Korherr worked out of Adolf Eichmann’s office in Berlin and had access to all his records relating to immigration and deportations. Korherr prepared a 16-page report, chillingly entitled “The Final Solution of the European Jewish Question,” in which he tallied the losses and additions in the Jewish population under Nazi control, 1933-1943. He calculated the changes in the Jewish population due to immigration, deaths, births, and evacuations and also documented the current location of the remaining living Jews (concentration camps, labor camps, jails, ghettos, etc.). He concluded that the total number of Jews under the influence of the Nazis had been “almost halved” in one decade, which included much of western Europe, post-Anschluss Austria, occupied Poland, the Baltic states, and the occupied Soviet territories. The original Jewish population for all these areas had been reduced by nearly 4,000,000.[5]

The fate of many of the Jews who had not managed to immigrate to countries and regions outside of German control (i.e. the United States, Central and South America, Palestine, Africa, Asia, and Australia) is made clear in a section of Korherr’s report entitled “Evacuation of the Jews.” He accounted for most of the “missing” Jews from western Europe and Poland in a chilling statistic entitled “Transportation of Jews from the Eastern provinces to the Russian East.” Researchers know that he was really talking about murder, not relocation. Korherr quotes Höfle’s exact figure (1,274,166) for the number of Jews that had been “pushed through” Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Majdanek. It is clear that Korherr had access to Höfle’s telegram at the time of his research and he felt Höfle’s figures were the most accurate available.

We know from existing documentation that Korherr’s final report was “sanitized,” so as to obscure the Nazis’ systematic murder of European Jewry. When Korherr submitted his first report to Himmler, he was notified that Himmler did not want “any reference to be made anywhere to ‘Special Treatment of the Jews.’” Nazi authorities provided Korherr with the exact wording he was supposed to use for the “evacuation” of Jews from the eastern provinces. He was to refer to these Jews as having been “processed through the camps in the Government-General.” Korherr was told that: “Another wording may not be used.”[6] Korherr dutifully changed the offending words and re-submitted the report. We do not know what Korherr’s exact wording was in the first draft of the report. The first draft has not been found. Still, the remaining documents, the letter telling Korherr what words to substitute and the final version of his report, are telling. When coupled with eyewitness testimony and forensic analysis of the death camp sites, it is obvious that murder was the business of these camps. Thus, the Korherr Report is a fairly accurate account regarding the number of Jews murdered in these camps. Likewise, Korherr appears to have made a mistake in his wording, a mistake that reflects the Nazi language of “Special Treatment.” Korherr did not replace one instance of the “Special Treatment” wording in his report. The common SS codeword for murder, “evacuated,” remains in a section of the report where Korherr listed the total of all Jews (1,873,549) who had been “evacuated” to the East.[7]

What do Holocaust deniers say about the Korherr Report?

The Holocaust deniers try to shred the credibility of the Korherr Report in a variety of ways, ultimately claiming that the Report provides “no explicit evidence” of a policy of “Judeocide.”[8] Overall, they claim that Korherr was incompetent and his figures are worthless. If their attack on the credibility of the Report doesn’t work, then they claim that Korherr padded the figures for immigration and evacuation to allow Himmler to impress Hitler with his efficiency. Finally, if the attack on Korherr’s competency and credibility fails, then deniers allege that someone tampered with the document after the war. They suggest that some unnamed party must have sought to pin the charge of genocide on the Germans.[9]

How do we know the Korherr Report is trustworthy?

The accuracy of Korherr’s figures can be seen in his calculations for the Jews deported from France by December 31, 1942. The French transport lists still exist and are well-documented, including the names, nationalities, birth dates, and birth places for every deported Jew. The figure compiled from the transport lists totals 41,941. Korherr’s figure is 41,911. The difference is 30. Korherr’s figure for Belgian Jews is 16,886, while the total from the actual transport lists is 16,861. This is a difference of 25 people.[10] These differences are minuscule and prove that Korherr was working with reliable German documents.

Recall too that Korherr quotes the Höfle telegram exactly, providing Höfle’s figure for the number of Jews (1,274,166) that had been “pushed through” Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka and Majdanek. There is no “padding” here—the figures come straight from numbers compiled by other officials.

Thus, Korherr’s figures are quite accurate and the claims made by Holocaust deniers are simply wrong. Similarly, when Holocaust deniers suggest that someone tampered with a document, like the Korherr Report, after the war, they employ a common diversion tactic for which they have no proof. Deniers simply assert that any document that does not support their assertions must be a forgery or it has been tampered with. There is no evidence that anyone ever tampered with the Korherr Report in any way.

Conclusion:

The claims of Holocaust deniers are false. The figures for the number of Jews murdered in the Operation Reinhard camps were not “simply invented” or “plucked from thin air.” Accurate research, based on Nazi documentation, shows that the Nazis and their collaborators murdered around 1,400,000 Jews at Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor.

NOTES

[1] Carlo Mattogno and Jürgen Graf, Treblinka: Extermination Camp or Transit Camp? (Theses & Dissertations Press, 2004), p. 101 at http://vho.org/dl/ENG/t.pdf. See also Mark Weber and Andrew Allen, “Wartime Aerial Photos of Treblinka Cast New Doubt on ‘Death Camp’ Claims,” Journal for Historical Review, Summer 1992 (Vol. 12, No. 2), pp. 133-158 at http://www.ihr.org/jhr/v12/v12p133_Allen.html.

[2] Peter Witte and Stephen Tyas, “A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during ‘Einsatz Reinhardt’ 1942,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, V15, N3, Winter 2001, p. 472. The article can be read in full at http://www.rodoh.us/052003-02282012arch11101961/arts/arts1/witte2001/witte-tyas_hgs2001-468.pdf.

[3] Jules Schelvis, Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp (Berg, 2007), pp. 197-229.

[4] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka” The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), Appendix A, pp. 381-398. See also Sybil Milton, translator, The Stroop Report: The Jewish Quarter of Warsaw Is No More! (Pantheon Books, 1979), Report dated May 24, 1943.

[5] “The Korherr Report” at http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?p=2097&sid=e1c472e6de9afcd87ee33c811089e651. The Report in German can be found at http://www.ns-archiv.de/verfolgung/korherr/korherr-lang.php.

[6] “Richard ‘I Didn’t know’ Korherr” at http://holocaustcontroversies.blogspot.com/2007/04/richard-i-didnt-know-korherr.html.

[7] “The Korherr Report”.

[8] Stephen Challen, Richard Korherr and His Reports (Cromwell Press, 1993), p. 42.

[9] Stephen Challen, Richard Korherr and His Reports (Cromwell Press, 1993), p. 43.

[10] Georges Wellers, “The Number of Victims and the Korherr Report” in Serge Klarsfeld, editor, The Holocaust and the Neo-Nazi Mythomania, pp. 148-149.